Concentration Limits – Take a Strategic View

10 minute read – While meeting regulatory requirements is important, an effective concentration risk management process should connect with the financial institution’s strategy and business model – not simply be a checklist of limits.

Set Limits Against Capital or Assets?

Financial regulators have stated a preference for setting concentration limits as a percent of capital, however, some financial institutions have felt more comfortable setting limits as a percent of assets. Measuring limits as a percent of assets feels more intuitive for some people, as many other ratios and limits are set as percent of assets, but this approach can have unintended consequences.

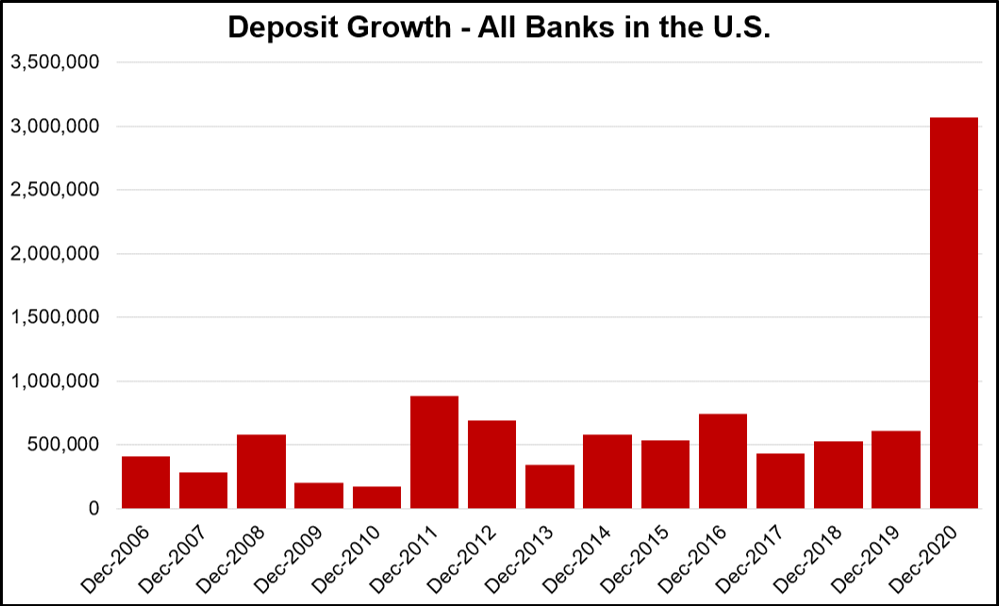

Consider that, over the last year, assets have increased at a record pace for both banks and credit unions, while growth in capital has lagged far behind. In 2020, bank deposits grew by more than $3 trillion. The $3 trillion in deposit growth represented a 24% increase in deposits and contributed to almost a 20% increase in total assets.

Credit unions grew at a similar rate on a percentage basis. If concentration limits were set as a percent of assets, then specific asset categories could have also increased 20% without triggering any flags or exceeding limits.

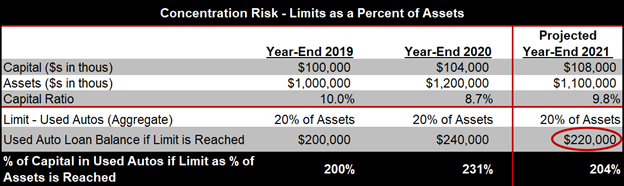

However, while total assets grew nearly 20%, bank capital only grew about 4%. If concentration policy limits were set as a percent of assets, then those balance sheet categories could have increased at a much faster rate than capital. In the following example, 2020 growth trends could allow used auto loans to increase from 200% to 231% of capital, allowing an institution to take more risk than what they may have intended.

Conversely, if assets decreased over the course of 2021, the institution in this example could find itself in a position where it would need to reduce balances in used autos by $20 million to stay within its 20% of assets limit or operate outside of policy, potentially causing an unintended swing in balance sheet strategy. The potential of having to reduce used autos to stay within policy limits could be painful, depending on the operating environment at that time.

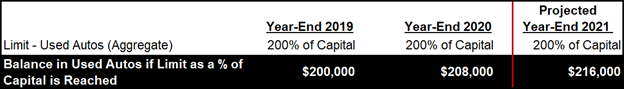

Using the same example, if the limits were set against the institution’s capital, then used autos could continue to increase regardless of what is happening with assets, as long as the capital is increasing.

If you currently have some or all of your limits set as a percent of assets, it would be wise to have a conversation around the potential challenges of that approach. Percent of asset limits could allow your institution to take a lot more exposure today, even though your actual capital dollars may not have changed much in recent quarters. On the other hand, if assets decreased, then asset-based limits could require reducing risk exposures even if capital is increasing.

Establishing Limits – Aggregate Risks to Capital Does Matter

As demonstrated in the examples above, decision-makers should consider setting limits against the backdrop of their capital strength. An institution with more capital may determine that they have more room to take on larger positions in higher risk assets, and vice versa.

A key question is, does your institution have enough capital to support the risks being taken?

First, it is important to understand the totality of the risk in the financial structure today and how much potential capital could be put at risk. Then, set limits that are complementary to ensure that there is never too much risk at one time measured against your institution’s capital while allowing for balance sheet flexibility. (Note that the limits are designed to be upper bounds, not a targeted or desired financial structure.)

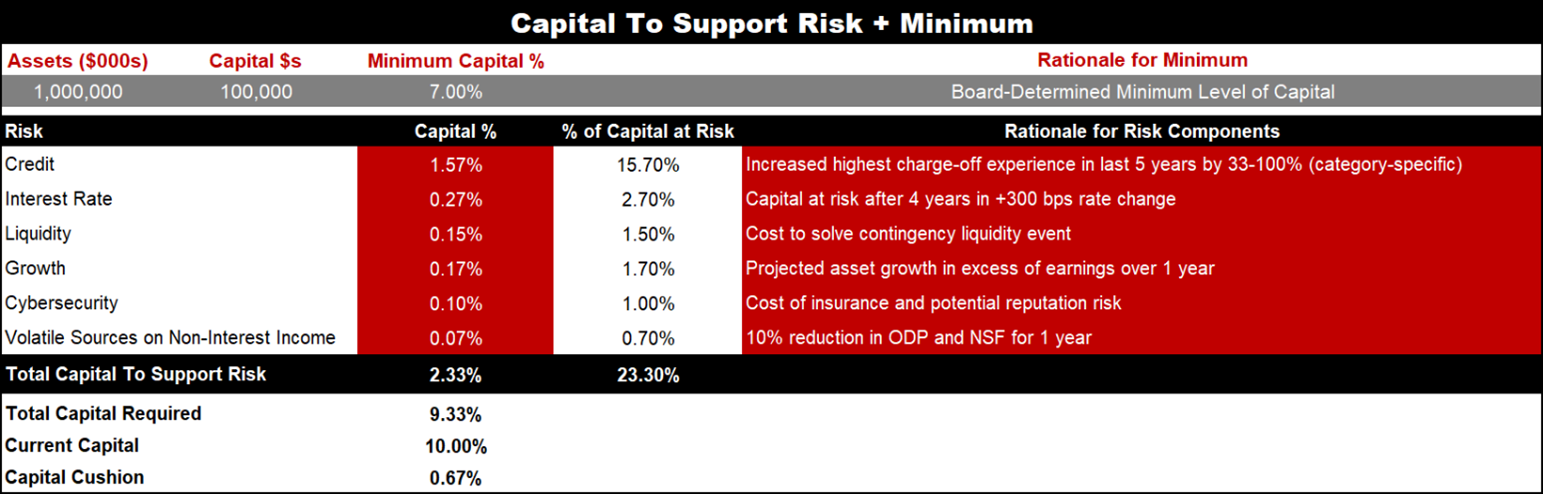

Consider the following example of a financial institution that has 10% capital and has gone through a process to identify the amount of capital dollars that could be at risk from a range of different risk events. The analysis showed this institution could put 2.33% of assets, or 23.3% of capital at risk from credit risk, liquidity risk, and cybersecurity – among others.

If this institution’s minimum level of capital was 7%, then after aggregating the different risk exposures, there would be a 0.67% capital cushion left over. If their capital decreased to 9.0%, the cushion would become a 0.33% deficit. As noted earlier, connecting limits to capital gives a more effective early warning indicator on whether the risk in the structure is in sync with the institution’s level of capital.

What Types of Risks Are You Protecting Against?

Having a strategic discussion to determine, articulate, and prioritize the different types of risks embedded in your institution’s business lines is another key step in the process of setting concentration limits. Establishing triggers in addition to limits can reduce stress and provide an early warning if limits are in danger of being crossed. The triggers are an effective way to have the appropriate discussions, timely.

Since every financial institution is different, concentration limits should be set based on each institution’s unique structure and strategy.

It is also important to understand how these risks may be interdependent so that you establish limits that protect your institution, but don’t tie your hands from a strategic standpoint. As the external environment changes, sometimes established limits can have unintended consequences of limiting business lines for the wrong reasons.

In addition to credit risk, and setting limits on credit risk “hot spots”, the following list highlights other considerations when establishing concentration limits. When documenting the limits, be sure to document the type of risk you are protecting against.

- Interest rate risk (IRR) – Are your interest rate risk concentration limits synced up with your ALM analysis and policy? It can be easy to have these two limits conflict or severely limit your options if the limits in the ALM policy, combined with concentration limits, result in unnecessary volume restraints.

- Business risk – Does your institution have unique business risks, such as, a material reliance on a particular type of lending that could be quicky and significantly impacted due to competition or regulation?

- Liquidity risk – If your institution has any significant exposures to illiquid assets, rate-sensitive deposits, or runs lean from a liquidity perspective, then identifying and managing liquidity risks should also be considered when evaluating and setting concentration risk limits. Just like with interest rate risk, any liquidity-related concentration limits should be in sync with other liquidity analysis or policies that are in place to avoid conflicts or unnecessary overlap.

- Speed and pace of growth – Monitoring the speed and pace of growth of certain assets and liabilities should be analyzed. It is also good practice to establish triggers. The primary purpose of the trigger is to promote discussion and further evaluation so that the speed and rate of growth does not get out of control.

What Else?

Does your institution engage in business activities that fall outside of these areas, but could create substantial risk of loss or risk of reduced revenue? For example, the last 15 months have put on display some dramatic swings in non-interest income. Early in the pandemic, both interchange and overdraft protection (ODP) declined significantly. For many institutions interchange has rebounded, but ODP is still far below pre-pandemic levels. Financial institutions with a heavy reliance on generating non-interest income should, at the very least, have a conversation around their reliance and susceptibility to reductions in non-interest revenue.

Many institutions also set limits to not exceed exposure levels specified by regulation. While this may seem obvious, having regulatory limits in the concentration risk policy can help make things easier to manage by keeping all key concentration limits in one document.

Too Many Limits?

Setting policy limits is always a delicate balance between managing risks and optimizing opportunities. Some financial institutions have inadvertently handcuffed themselves with policies that are extremely detailed, setting limits on almost every conceivable asset or liability, regardless of whether there is any substantial risk of loss. Consider, do all of your concentration risk limits serve a purpose, or are some just filling space in the policy?

What loan categories have caused losses in the past, or have the potential to cause substantial losses in the future? Putting energy into understanding the risk in those areas can help make the analysis and the limits much more effective.

Tying It All Together

Finally, step back and make sure that your different policies work together. As noted earlier, boundaries on interest rate risk should be part of the ALM process, and duplicating IRR efforts between concentration and ALM policies can create unintended consequences and missed opportunities.

For example, it is not uncommon for an IRR analysis to show there is room to take more risk, but opportunities need to be passed over because of an IRR-focused concentration limit. This often happens with mortgage-related assets. An institution may have to forgo holding mortgages to members because of too much concentration in variable GNMA mortgage-backed security investments. Are the risk exposures of a variable GNMA pool the same as a fixed-rate mortgage made to a member?

So, what risks are you concerned about that could threaten the safety and soundness of your institution? Decision-makers need to define the risks, test, understand exposures, set reasonable limits against the backdrop of capital, and, most importantly, evaluate the risks to capital in aggregate. Finding the right balance is not easy, but taking the extra time to make sure concentration limits are manageable and fit with the rest of the institution’s strategy is a worthwhile exercise.