Long-Term CDs – Questionable Cost of Funds Protection

The 10-year Treasury closed below 1.40% 3 days in July!

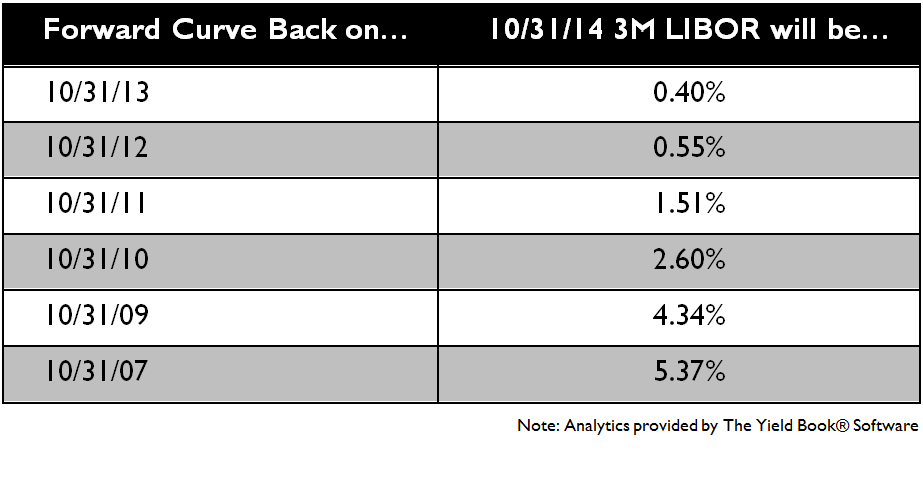

The flattening of the yield curve has many folks worried about further pressure on net interest margins. Some, though, are hoping to extract a benefit by locking in long-term funding at historically low interest rates. As an Asset/Liability Management (A/LM) strategy, this approach employs the trade-off between paying something more today for protection in a potential rising rate environment in the future.

The use of long-term, competitively priced Certificates of Deposit (CDs) is one common approach to achieving this goal. But there are risks in making that strategy work.

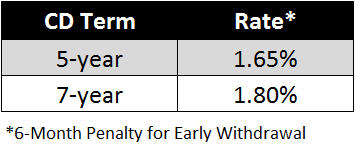

Consider a credit union offering these competitive CD rates:

A member selects the 7-year CD earning 1.80% and invests $100,000. At the end of 2 years, the credit union has paid $3,600 in interest on the CD as expected. The credit union and the member are happy. Then, at the end of year 2, CD market interest rates increase by 100 bps.

A member selects the 7-year CD earning 1.80% and invests $100,000. At the end of 2 years, the credit union has paid $3,600 in interest on the CD as expected. The credit union and the member are happy. Then, at the end of year 2, CD market interest rates increase by 100 bps.

How would a member be expected to react?

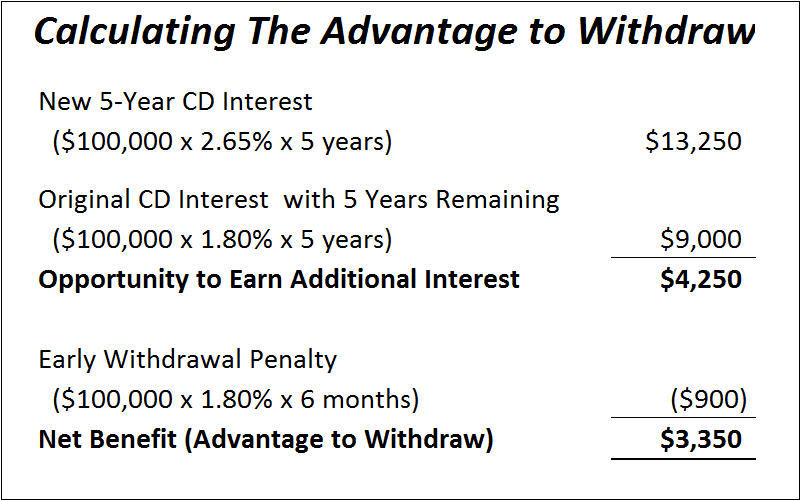

With 5 years remaining in the term, a comparable 5-year CD would be about 2.65% (1.65%

With 5 years remaining in the term, a comparable 5-year CD would be about 2.65% (1.65%

from the table above plus the 100 bp market interest rate increase), versus the 1.80% currently being earned.- The difference of 85 bps equates to an opportunity to earn an additional $4,250 over the remaining term.

- The member must also pay the early withdrawal penalty of 6 months interest, which equates to $900.

- A net benefit to the member (advantage to withdraw) of $3,350 is left to pay off the original CD and reinvest in the new CD.

- Considering the financial analysis, the member opts to pay the penalty and closes the CD.

The credit union paid the member a higher CD rate during the first 2 years for protection it did not receive in years 3-7 when CD market interest rates had increased.

Why did the strategy not work?

The opportunity to earn more interest on a new CD when market interest rates increased greatly outweighed the penalty to early withdrawal. This is an issue for any long-term CDs that include an option for early withdrawal. If market interest rates become more favorable early into the life of the CD, the number of years remaining will often create a benefit that outweighs typical early withdrawal penalties. Contributing to the issue is the flat yield curve, which means even small market interest rate increases can create a net member benefit using shorter-term CDs.

In fact, using the example above, at the beginning of the 7-year term the market interest rate would only need to go up 13 bps for there to be an advantage for the member to withdraw early.

By the end of year 2, with 5 years remaining on the CD, the rate would only need to go up 19 bps.

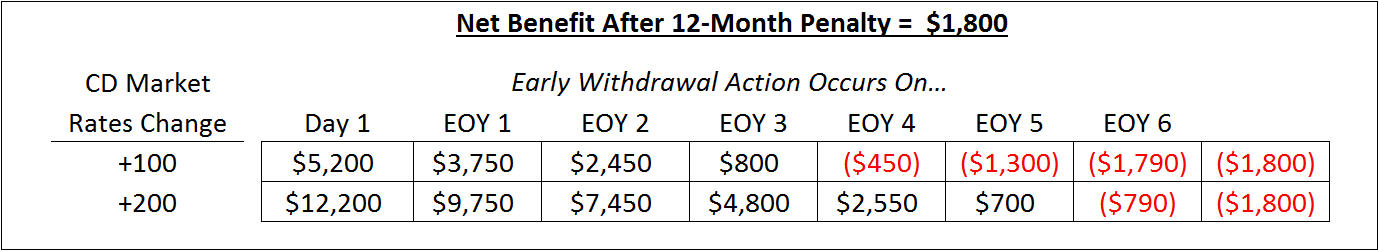

Consider again the 7-year $100,000 CD, and let’s look at the net benefit to the member each year if CD market interest rates changed by +100 bps or +200 bps. The net benefit is calculated simply as:

- New CD expected lifetime interest earned (keeping the overall maturity at the original 7 years)

- Minus the existing CD interest lost through maturity by closing the CD

- Minus the early withdrawal penalty

In the table above, notice that when using a 6-month penalty, the member benefit is positive until the end of year 4 for a +100 bp rate increase. This means that if the CD market interest rate were to go up by 100 bps in any of the first 4 years, the member could reasonably be expected to close the CD. Beyond the end of year 5, in a +100 bp rate increase, the early withdrawal penalty provides a disincentive to close the CD. Notice too, that a 6-month early withdrawal penalty leaves the member with a positive benefit through year 6 in a +200 bp rate increase.

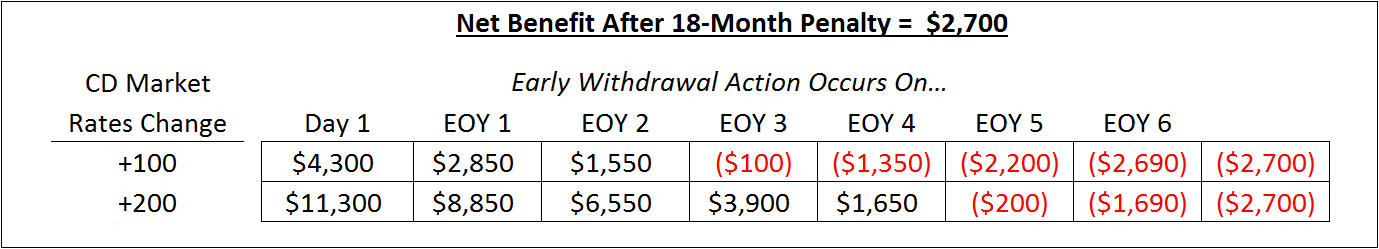

The following tables increase the penalty by an additional 6 months each. A 12-month penalty creates disincentive after 3 years in a +100 bp rate in increase, and begins to create some disincentive after 5 years in a +200 bp rate increase. An 18-month penalty encourages the member to stay in the CD for 2 years in a +100 bp rate change.

The point is that the longer the CD, the more difficult it can be to design it to provide effective cost of funds protection in a rising interest rate environment. Typical early withdrawal penalties are not likely to be enough to make the interest rate risk strategy successful.

Credit unions may need to consider stiffer penalties for members that want to lock in a long-term investment. If the objective is risk mitigation, an option could be to have the penalty be half the term. Another option that is more complicated to explain and disclose, is to have the penalty equal to the replacement cost (present value). Each option has a trade-off and it is important to balance member perspective. An option is to have a materially lower rate with the traditional penalty and then label the more aggressive rate an investment CD (stiffer penalty). Of course, management might also consider other A/LM tools, such as long-term, non-callable borrowings, to help protect the cost of funds in a rising rate environment.