Observations from ALM Model Validations: NEV – Loans Devalue in Rate Shocks – or Do They?

When considering valuation as a measure of interest rate risk, and value volatility as an indicator of changes in interest rate risk, many institutions perform net economic value (NEV) analysis. When working with credit unions, or performing model validations, a concern many have is ensuring the models have the “right” assumptions. What is the “right” discount rate? Should credit risk spreads be incorporated? What effective discount rate or what yield curve should be used to discount cash flows – which method is “more right”?

All of the above may be questions to consider but they are distractions from simple analyses credit union management teams can perform when determining if answers are reasonable. For example, take an auto loan portfolio in which the valuation methodology derives a value of $210M in the base rate environment. This same portfolio devalues to $200M in a +300 bp shock. Said differently, the value volatility in a +300 bp shock is -5.00%. From a quick reasonableness test, this is within a 4-6% devaluation range in a +300 bp shock – very reasonable for an auto loan portfolio.

However, does it change the reasonableness answer if the current book value of the auto loans is $199M? While the devaluation of the loan portfolio is certainly reasonable, the resulting answer implies that the loan portfolio could be sold at a 0.50% gain if rates increased 300 bps instantly. That answer is certainly less reasonable. It is important to remember, in Chapter 13 of NCUA’s Examiner’s Guide, NEV is defined as the fair value of assets less the fair value of liabilities. Would it be reasonable to assume a fair value gain on an auto loan portfolio if rates increased 300 bps?

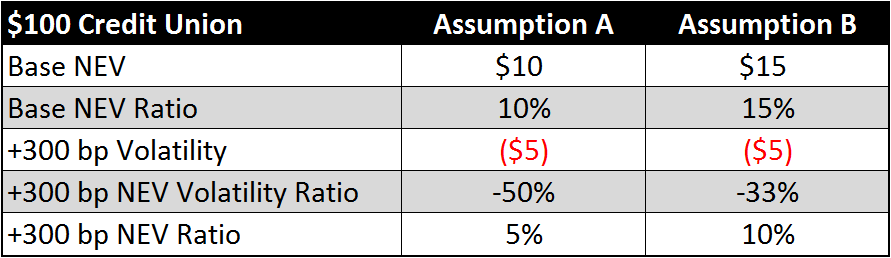

When measuring NEV volatility, the starting value still matters. High starting values can be driven by low starting discount rates. It is good to evaluate both the effective discount rate and the difference between value and book in the current environment. Some models are unable to calculate an effective discount rate. We have found that sometimes in this situation the effective discount rate does not match what the user intended. If you are in the situation of the model not being able to show the current discount rate, extra attention should be given to the value versus book and how the value compares to book in different environments. Optimistically high starting and shocked values can hide risk and volatility; this connects with the cautions brought out in our blog regarding high starting NEV ratios posted on September 25, 2015.